如何在7天內快速完成游戲原型設計

2020-07-15 10:40 風色年代 閱讀(915) 評論(0) 收藏 舉報原文鏈接: 如何在7天內快速完成游戲原型設計

作者:Shalin Shodhan、Matt Kucic、Kyle Gray、Kyle Gabler

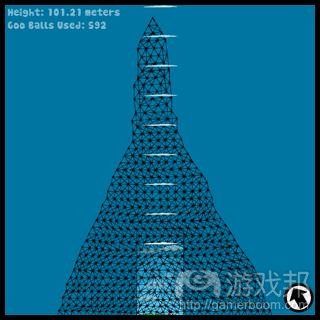

這是一個瘋狂的游戲創意:用一大堆的納豆似的黏黏球搭成一座高塔,越高越好。這些壞笑著的黑球一個踩著另一個地往上爬,直到抵達收集管口。這是一場小球與大球的斗爭——如果你的塔堆得不夠穩,它就會因地心引力而倒塌。《黏黏之塔》這款游戲在一個月內破天荒地超過了10萬個下載,被某雜志封為”當月網絡最佳游戲“。這些貌不驚人的小黏球因此登上G4電視頻道、進入GDC大會的“Experimental Gameplay Workshop ”。其實《黏黏之塔》只是我們制作的50多個游戲中的一個,而這50多個游戲也只是我們在卡內基梅隆大學娛樂技術中心進行的娛樂游戲項目的一部分。

這50多個游戲都是1個人用僅僅1周的時間完成的。

2005年的春天,我們萌生了一個念頭:發現并且快速原型化盡可能多的新型游戲玩法。四個大學生組成的項目小組運應而生。我們在房間里“閉關修煉“了一個學期。以下是我們的“修煉法則“:

1、每一款游戲的制作必須在7天以內。

2、每一款游戲只能由一個人獨立完成。

3、每一款游戲 都必須圍繞共同的主題,如“重力”、“植物”、“群體”等等。

隨著項目的運作,網站的流量水漲船高,吸引了游戲雜志和業內專家學者的目光,他們紛紛向我們求真相、求秘訣。

在此我們就把經驗公之于眾。根據下文提出的技巧、訣竅和例子,我們將探討哪些方法管用,哪些方法無效。此外,我們還會告訴你如何養成制作原型的心態、如何組成有效的團隊、如何在不確定時起步新構想。但愿我們的這些經過考驗的指導能或多或少給你帶來一點啟發!

為了便于瀏覽閱讀,所有的技巧和訣竅都規納為四個部分:計劃、設計、開發和常規玩法。

1、計劃:速度是一種心態

快速原型在制作前期不止是一種實用工具,更是一種生活方式!以下我們來談談如何像個快速原型達人一樣計劃和思考。

從容接受失敗的可能——鼓勵接納創意的風險

我們所謂的麻煩制造者就是”風險“。可以說,因為害怕失敗,所以誕生了保守的電影改編或授權游戲。這就好比,你總是習慣性地選擇麥當勞,而不是尋街竄巷地尋找新餐館——因為眾所周知的品牌總是比那些雖然可能供應美味食品的不知名小店更保險。

快速原型的達人應該明白失敗沒什么大不了!制作原型很大程度上就是為了找出失敗的地方。如果你失敗了,意味著你將吸取更多經驗教訓。所以,從容地接受失敗的可能性,有益的實驗探索才成為可能。

Gray:“《Mime After Mime》和《A Mime to Kill》是兩款只有聲音線索而沒有圖像線索的游戲。盡管它們都是大敗筆,但整個團隊由此證實了純聲音玩法的失敗。我可以大方地承認,這是我的‘杰作’。因為我從整個項目中積累了經驗,以后我可以大膽地冒險,因為我所冒的險都指向成功的方向。”

縮短開發周期(時間不等于質量!)

短短數天足矣。你理所當然地認為:“如果用一周的時間可以開發一款好游戲,那么,如果我們花了兩周,游戲就應該好上加好!“當然,這不是真相。我們發現,通常情況下,1周的時間足夠有效地完成任何游戲想法的原型。開發時間與成品效果成反比。例如有些原型的制作只需要1個晚上,而有些則需要耗費1周。我們驚訝地發現,開發時間與游戲的最終成功沒有必然聯系。

如上對比圖所示,《Attack of the Killer Swarm》(左)只用了一天時間就拼湊出來了,出乎意料地成為項目中得分最高的游戲之一。《Suburban Brawl》(右)多費了一個星期的精力去制作,結果卻使游戲更加繁瑣了;如果沒有巨型殺手機器人(另一個時間和設計浪費),這款游戲也許會更有趣。

限制創意范圍

我們最成功的游戲帶有特定的主題,如“玩具”、“重力”、“群體”或“以女性休閑玩家為目標人群”。不知為何,當存在這種限制性條件時,創意反而更容易了。

另外,整個團隊的人同時圍繞一個特定的主題展開原型制作,一方面,我們可以保證避免撞上相同的玩法機制;另一方面,我們積極地探索所有游戲玩法的可能性,幾乎涉獵了所有游戲主題。

在項目即將結束之際,我們拋開這種模式,結果被狠狠地教訓了。所以我們得出的經驗是:如果沒有可靠的主題限制,游戲的制作時間將更漫長、方向更加搖擺不定,最終損害團體合作。“我們是密不可分的整體”這種感覺被沖淡了,甚至更慘,把激發創意和技藝的友好競爭的心態也毀掉了。

我們探索過的主題有“重力”、“彈簧”、“聲音”、“掠食者和獵物”、“致癮性游戲”、“繪圖”、“指數增長”、“植物”、“平衡”等等等。

組織一支優秀的團隊加一名目標顧問——心態和才能同等重要

團隊的各名成員必須對游戲開發的方方面面都感到舒心順意。每個人都各自負責自己的編程、美工、音效等所有最終成品元素。這個各人才能的體現,但才能不等于一切。理想情況下,每個人都有必須帶著設計本身是至高無上的理解參與開發工作——因為其他一切,從美術到引擎,都是服務于最終設計。欠缺這種心態的優秀工程師并不會比深諳此道的平庸工程師成功多少。

項目顧問Jesse Schell曾提到:“我總是癡迷于生成新游戲創意的過程,所以自然而然地,當 Shalin、Matt和 Kyles提議這個項目時,我心花怒放。抱著從中學到實用的游戲設計經驗,我把這個項目當作在創意過程中同步進行控制性實驗的嘗試機會。作為學院顧問,我努力確保團隊嘗試若干不同的技術、從錯誤中吸取教訓、避免固守無效的設計想法、找到個人最理想的創意途徑。

我也對優化游戲提出建議,但基本上我只是旁觀者。我有點兒像園丁——只是負責一點灑水和除草的工作,花朵怎么長完全靠自己。正如本文所示,這支隊伍能夠得出非常有用的結論,最終制作出一些非常棒的游戲!如何升級創意過程仍然有待進一步探索,卡內基梅隆娛樂技術中心打算繼續開展這個項目。”

同步開發

組成一支團隊后,然后呢?我們不再孤軍奮戰了,但也不是并肩作戰!也許聽起來有點奇怪,但非合作的團隊形式使我們受益匪淺:

1、風險消減:因為我們同時制作四個游戲原型,所以我們不怕冒險,至少有一兩款非常可能成功吧!

2、友好競爭:“各人自掃門前雪”的合作確實對大家都好,跟資本主義的成長一個道理!

3、更廣的主題探索:四個人的心思都放在同一個主題上,迫使我們深入探究各個主題。如果我們做的游戲都是一個模子出來的,那也太諷刺了吧!所以我們就不得不探索其他創意范圍,避免“撞車”。

4、共享和關注:雖然我們并不共享代碼(非必要條件),但我們發現分享概念和理解累積的知識非常有好處。比如,如果成員之一發現了展現彈簧系統的有效方法,所有人都能從共享中受益。

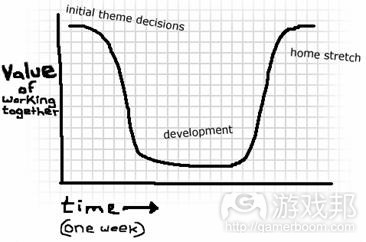

數周下來,我們還發現,團隊合作在開發過程的初期效益最高——團隊合作能夠促進提煉和比較游戲創意。一旦開發進入正軌,因為各個成員都全心全意地投入到自己的工作中,大家就不會再受到其他成員的干擾。在周期的末尾,我們會回歸團隊,齊聚一堂直到友好競爭的最后一秒在晨光中消逝。以下是團隊合作效益的曲線圖。

2、設計:創意與集體討論的神話

絕妙的想法往往迸發在一瞬間,但等待靈感的火花閃現是一段很折磨的過程。世界上不存在能擠出創意的力量,但至少我們可以培養自己的創意精神。

常規的集體討論,成功率為0

我們非常努力——我們真的希望集體討論這種東西能管用!我們按時舉行“頭腦風暴”會議,我們在白板上嘗試了不同的色彩標記和便利貼,我們甚至利用激發性短語,如”藍天“,以幫助跳出框架進行創造性思考。但最終,我們制作的所有游戲,沒有一款歸功于大家團團圍坐一起的集體討論。

為什么?我們非常震驚,但經過多次研究發現,創意是沒法規劃的。你不能說:“嘿,4:15 是我們的頭腦風暴時間,5:00我們將誕生4個了不起的游戲創意!”

但頭腦風暴也非全無希望,組織妥善的集體討論對話可以給你(至少)兩個合理的指望。第一,讓所有人都開動腦筋。之后,可能是開車回家、或者是沖涼、或者是遛狗的時候,頭腦中靈光一現,偉大的游戲創意誕生了(游戲邦注:當然,也可能什么也沒發生)。據我們所知,神秘的大腦通常是在你不怎么抱幻想的時候才積極地運轉。

第二,當具體的問題擺在大家眼下時,頭腦風暴式的會談就能看出效果了。例如,“怎么改進這一點?”和“隨便想點什么吧!”二者相比,顯然前者更有探討價值。又如,已知一個半成品的游戲創意,讓團隊的其他成員在集體討論中繼續充實它,往往能取得良好的效果。相對于創作者,人們通常更勝任批判者,對吧?

利用概念藝術和音樂激發情緒目標

除了集體討論,我們發現帶著個人意識去收集藝術和音樂也是卓有成效的方法。有人曾評論許多游戲,如《Gravity Head》和《On a Rainy Day》等創造了一種強烈的感性氛圍,且具有強大的情緒激發能力。這絕非偶然。在許多情況下,聲軌和初期美工創造了一種混合性感覺,這種感覺決定了之后的游戲玩法設定、劇情和最終美術風格。

Gabler:“走回家后,我正在欣賞Astor Piazzolla的《熱情探戈》的開頭時,突然冒出了《黏黏之塔》的創意。在我模糊的想像中,日落的天空下有一座塔,人們從自己的房子里拖出椅子、桌子和所有可以堆成高塔的東西,集合到市中心。我確實不知道為什么,但他們就是一心想往上爬、爬、爬——但他們不是合格的工程師,所以你得幫他們一把。游戲的最終原型更加活潑。我把最終音樂換成 了Piazzolla的《自由探戈》,這一曲比前一曲的節奏更快。但最初的情緒基本上渲染完了整個游戲。”

腦內模擬——原型前期的原型

這太容易了!你要做的就是想象一下你的游戲玩家叫道:“哇!”然后繼續填充空白的地方,即想象玩家為什么喜歡你的游戲?他們的感覺如何?游戲怎么讓他們產生那種感覺?

我們最成功的游戲,好玩是理所當然的——在最理想的情況下,還沒完成代碼,我們就知道它肯定有趣,因為我們已經提前對游戲進行了想象性實驗。反之亦然。從來沒有什么游戲能夠超脫我們的想象,突然地或出乎意料地就成功了。我們總是先知先覺。(游戲邦注:但不幸的是,這種先知先覺不能讓我們堅持對半成品的創意深究。)

在頭腦中模擬確實能簡化最終原型的開發。因為你知道你將做什么,你不必浪費時間進行反復的測試性和錯誤性“設計決定”。

團隊成員之一承認:“一周的頭三四天,我們像傻子似地圍坐著看O-Zone組合的音樂視頻,巴望得到‘靈感’,或者在懶人沙發上東倒西歪地聽著音樂,一邊在腦中模擬游戲畫面,這些都不算稀奇。最后,大約周四或周五,我痛苦了,因為我還是沒法在周一交差,所以我就從所有想法中選了最強烈的那個,不管是什么,努力把它擴充至像個有趣的游戲就是了。然后,我徹夜不眠了若干天,把它的代碼敲進電腦、畫出精美的圖案。對我而言,(我認為其實是我們四個)花在制作前期的時間毫無疑問,比實際開發的時間更有價值。”

3、開發:沒人知道、沒人關心你怎么做

首先構建“玩具”

從核心機制開始。無論是彈簧系統、群體活動、引力還是其他等等,絕對不需要數小時來展示基本的游戲主題。所謂的“玩具”應該是游戲的核心機制減去所有目標或決斷。沒有輸贏的差別,純粹到是一款有趣的游戲。

Gabler:“《Super Tummy Bubble》的‘玩具’就是一堆懸浮在小容器中的泡泡。猛按這些泡泡一會兒之后,我徹底沉浸于戳泡泡的滿足感之中,所以,是時候敲定其他游戲設定了。在此,游戲的特點就是寄生著不同蟲子的泡泡、”爆“的概念、”鏈“的概念、計分器等等。”

如果可以,那就蒙混過關吧

這個項目告訴我們最重要的一課是,“改正”法通常不是最佳解決方案。從戰略上講,蒙混可以節省時間和資金;可以使游戲運轉得更快;可以讓你的牙長得更白(你不會因為通宵加班而不刷牙了)。所以,自由隨意地混吧!當簡單的投影和光照紋理湊效(《Darwin Hill》)時,就不要使用復雜的光影效果。如果你可以用相同的效果來制作(《Suburban Brawl》),就不要設置復雜的圖形識別系統來分析玩家的繪圖。如果粗制的位圖能夠更快更容易地達到相同的效果(《黏黏之塔》),就不要畫曲線或自創矢量圖案庫。我們發現這同樣是一條不可思議的生活法則。懶人們,記下吧。

避免不必要的損失

項目運轉之初,大家都力求圓滿——耗費更多時間和精力確保一款糟糕的游戲能變成天才的杰作。例如,我們制作了一個彈簧系統,你可以擠壓它、伸展它、擺弄它,但它就是沒有長成一款吸引人的游戲。最初的彈簧系統不過數小時的時間就完成了,但之后它瘋狂地吞噬了一整個星期的時間——不斷地編碼再編碼,為的就是最終能把這個系統折騰成一款游戲。

你必須對走進死胡同的游戲創意保持先知先覺,然后盡可能減少自己的損失,不要在一個想法上死磕。正如我們所發現的,順其自然遠比大費周章地改寫已有的代碼更有價值。只要靈感在,就不怕返工回頭。

Kucic:“我的‘土豆’是一個由 Flash做成的完美的軟體模擬系統。美中不足的是,我沒辦法讓它變得有趣。它讓我頭疼,浪費了一星期卻毫無進展。你得知道什么時候堅持什么時候放棄。”

再好的主題也不能挽救差勁的游戲

玩家遠比你所想象的聰明,如果你耍花招,群從雪亮的目光絕不會放過你。如果游戲玩法太爛,那游戲就基本無藥可救了——什么美工、音樂、周邊搭賣全都無效。就像使用3D動畫來掩飾拙笨的玩法機制,怎么可能逃過玩家的法眼?

Gray: “《Spin to Win》的玩法就在于轉動鼠標來旋轉圈圈——其實就是旋轉唱片。為了掩飾無趣的事實,我大量使用《家有仙妻》似的風格和音樂擴充游戲的主題。但無論我怎么打磨這款游戲,它就是成不了發光的金子。盡管我對它寄予厚望,它還是很快淪為我們的網站上最令人討厭的游戲。”

合理利用美術設計、音效和音樂

這點其實有悖于我們最初的一個假想。我們曾認為美術設計和音效對游戲本身不能起多大的作用,但我們錯了!外部效果驚艷的游戲確實比內部代碼上乘但外部設計粗陋的游戲更加引人注目。你要記住的是,優化美術設計仍然不能挽救失敗的整體設計,但它確實能讓原本不錯的游戲錦上添花。這不是說你需要夢幻般華美的畫面或高超的立體音效,而是,你可以把一切合理的元素組合成緊密聯系的整體。記住,甚至“蹩腳”也可能通過合理使用其他元素而實現美學上的成功。

玩家不關心你的代碼

出色的工程師未必就是杰出的原型師。我們往往不能單純地指望用“正確的”或“可重復利用”的解決方案來對付一次性的代碼。對于任何問題,你應該想出盡可能多的解決方案,以達到兵來將擋、水來土淹的效果,也就是要快!終端用戶從來就不看你偉大的代碼,并且他們從來就不關心。

Shodhan:“過分的代碼設計,往往淪為平庸的工具或技術演示。這好比一個搖滾巨星自顧自地沉浸在自己非凡的技藝之中,毫不理會臺下的聽眾早已昏昏欲睡!對于”進化“主題,我編了一個通過雜交祖輩樹種來實現進化的3D效果。這其中運用了大量先進的技術,但和游戲性沒有半點關系!”

4、常規玩法:樂趣的感性課程

除了煞費苦心地學成快速原型,我們還要突破一些常規玩法。以下列舉了一些增加游戲“樂趣”的經驗。

復雜未必有趣

數千年以來,各種各樣的“球體與平面”的變體游戲就已經滿足了人們自娛自樂的需要,而今,我們大概在新奇的電子游戲領域里努力過頭了。人類完全有可能從最基本的幾何體中收獲樂趣,想想《俄羅斯方塊》、《吃豆人》和其他經典的街機游戲。正如《羅密歐與朱麗葉》的愛情故事原型總是被反復翻用,這些游戲的機制如此經典,所以數十年以來我們樂些不疲。鏡頭光暈、凹凸貼圖、攝相機等新技術雖然效果驚人,但并沒有使游戲更加有趣。如果你能讓自己堅信核心機制只是一個簡單的原型,那么你一定可以把游戲原型做得很好。

創造一種擁有的感覺

在非常偶然的情況下,我們發現能重復玩的游戲通常帶有某些自創或自定義特征。例如,“用手臂和傘做一棵嚇人的樹”、“我畫我家”,又或者“自成一塔”、再或者“獨家變形物種進化”。顯然,你可以在許多游戲的自定義頭像、自定義手機鈴聲和“展現獨特的自我”似的廣告營銷中發現這種眾所周知的現象。所以,緊跟潮流走吧!讓玩家產生一種擁有的感覺,從而成為游戲的“回頭客”。

“實驗性”不等于“復雜性”

在項目早期,我們所做的許多游戲都太過復雜。不僅UI令人迷惑不解,而且動作輸入也很別扭。除非我們可以在玩家搞清游戲之前就縮減玩家的摸索時間,否則玩家就可能大受打擊,再也不會玩這款游戲,甚至再也不光顧我們的網站。所幸,我們發現游戲可以具有實驗性,且仍然通俗易懂。

Shodhan: “我的第一個回合游戲《Spaceball Munc》是一個3D版的老式“大猩猩”游戲——玩家指定一個角度和一個力度,一只猩猩據此向另一只猩猩投擲香蕉。現在這款游戲不僅是3D的,而且還有弧形視角和球面力場。所以玩家就要兼顧兩個角度和一個力度。當然,現在它不是回合制游戲了,所以你得控制連續性系統的同時,必須擊中所有移動中的物品。以下截圖是關于物品被拋擲后的變化過程。

朝著明確的目標前進

令人難堪的是,明確的目標總是容易被遺忘。如果沒有玩法目標,原型就只是個玩具,稱不上真正意義上的游戲。出于某些原因,人們看似享受失敗的感覺。什么形式都可以看作目標——如“在某時間段內收集到多少多少工具”、或“保持系統穩定”、或“安然越過某空間”,但要找到一個不讓人覺得突兀的目標(如時限),談何容易?最佳目標是游戲玩法的固有部分,如《黏黏之塔》的隱藏目標就是單純地”搭建“。

游戲的“活力”

有“活力”的游戲就好像,當你觸及它們時,會彈起、扭動并發出一點聲響。有活力的游戲如有生命,能對你的所做所為做出反應——最小的用戶輸入換取最多的回應。它讓玩家感到對游戲世界的掌控感,從而訓練他們逐漸學會每一條游戲規則。

有些活力四射的例子你大概有所耳聞:

《 Alien Hominid 》:UFO墜毀在FBI門口之后發生的FBI與ET之間的戰斗,邪惡的血肉橫飛。

《超級馬里奧》:在一個充滿金幣的空間里上蹦下跳,金光閃閃啊。

《彈球盤》:控制不斷涌出的球體。

《 Super Puzzle Fighter II Turbo》:一款日式卡通風格的益智方塊游戲。

后記

實驗游戲玩法項目小組的合作令人熱血沸騰。我們希望下次你嘗試新事物時,我們的小技巧能夠派上用場。也許眼下你正在做的小事也有可能變成驚天神作呢。叫上些朋友或者單槍匹馬,著手制作游戲原型吧!你會讓自己都感到出乎意料。

我們的項目顧問指出:“快速原型非常像十月懷胎,沒人敢擔保肚子里的孩子一定是人中龍鳳,但你總是能從中得到新收獲和許多樂趣!”

最后,享受快速原型的樂趣!

游戲邦注:原文發表于2005年10月26日,所涉數據及時間均以當時為準。(本文為游戲邦/gamerboom.com編譯,如需轉載請聯系:游戲邦)

How to Prototype a Game in Under 7 Days

by Shalin Shodhan, Matt Kucic, Kyle Gray, Kyle Gabler

Here’s a crazy game idea: Drag trash-talkin’ gobs of goo to build a giant tower higher and higher. They squirm and giggle and climb upward over the backs of their brothers, but be careful! A constant battle against gravity, if you build a tower that’s too unstable, it will all fall down. “Tower of Goo” was downloaded over 100,000 times within months of hitting the net, it was dubbed “Internet Game of the Month” in one magazine, it was demoed on G4 and at the Experimental Gameplay Workshop at GDC, and it was one of over fifty games we made as a part of the Experimental Gameplay Project at Carnegie Mellon’s Entertainment Technology Center.

And like the rest of them, it was made in under a week, by one person.

The project started in Spring 2005 with the goal of discovering and rapidly prototyping as many new forms of gameplay as possible. A team of four grad students, we locked ourselves in a room for a semester with three rules:

“Tower of Goo” was downloaded over 100,000 times within months of hitting the net.

1. Each game must be made in less than seven days,

2. Each game must be made by exactly one person,

3. Each game must be based around a common theme i.e. “gravity”, “vegetation”, “swarms”, etc.

As the project progressed, we were amazed and thrilled with the onslaught of web traffic, with the attention from gaming magazines, and with industry professionals and academics all asking the same questions, “How are you making these games so quickly?” and “How can we do it too?”

We lay it all out here. Through the following tips, tricks, and examples, we will discuss the methods that worked and those that didn’t. We will show you how to slip into a rapid prototyping state of mind, how to set up an effective team, and where to start if you’ve thought about making something new, but weren’t sure how. We hope these well-tested guidelines come in useful for you and your next project, big or small!

For easy browsing, all tips and tricks are organized into four sections: Setup, Design, Development, and General Gameplay. Enjoy!

1. Setup: Rapid is a State of Mind

Rapid prototyping is more than just a useful tool in pre-production – it can be a way of life! This section will show how to set up and begin thinking like a rapid prototyper.

Embrace the Possibility of Failure – it Encourages Creative Risk Taking

It’s all about that little trouble-maker we call “risk”. Fear of failure, as far as we can tell, is the reason why movie licenses and double digit franchise games keep getting made. It’s like always choosing to go to McDonalds instead of an unexplored new restaurant – always safer to rely on a well-known adequate option rather than take that risky plunge into the unknown but potentially delicious.

A good rapid prototyper would realize that failure is ok! That’s what prototyping is for, so go crazy! If you fail, there will be dozens more, and chances are, you’ll learn something anyway. By embracing the possibility of failure, rewarding experimentation becomes possible.

Mr. Gray: “Mime After Mime” and “A Mime to Kill” were two games I made that attempted gameplay using only positional audio cues with no visuals. Although they were utter failures, the whole team was thrilled to take such a bold risk to prove the failure of audio-only gameplay, and I could point with pride to my hideous creations. As I gathered experience throughout the project, I was able to take more directed risks that lead to successful games.”

Enforce Short Development Cycles (More Time != More Quality)

You only need a few days. It seems like a natural and comforting thing to say, “Hey we made a great game in one week. Therefore, if we spend TWO weeks, it will be TWICE as good!” Of course this isn’t the case. We found that generally any gameplay idea can be prototyped effectively in less than one week. Extra slop time tends to yield diminishing returns. Some prototypes, for instance, took just a single evening to throw together, while others got an extra week or two of love. Surprisingly, we found that there was no correlation between time spent in development and how successful the game ultimately turned out.

Constrain Creativity to Make You Want it Even More

Our most successful games grew out of specific themes or “toys”, like “gravity” or “swarming” or “make a game targeted towards a predominantly female casual gamer demographic”. Somehow, it became easier to be creative when there were restrictions in place.

Additionally, with a team of people all simultaneously generating prototypes around a particular theme, there was some guarantee we would avoid attacking the same obvious gameplay mechanics. Instead, we were challenged to explore and really suck the theme dry for all possible gameplay uses.

We moved away from this model towards the end of the project, ultimately to our detriment. Without solid thematic constraints, the games took longer to create, had less direction, and group unity deteriorated. There was less a feeling of “we’re all in it together”, and even worse, we lost the sense of friendly competition that was responsible for squeezing out those extra drops of creativity and finesse.

Some of the themes we explored were: “gravity”, “springs”, “evolution”, “sound”, “predator and prey”, “addictive games”, “drawing”, “exponential growth”, “vegetation”, “balance”, and a few others individually.

Gather a Kickass Team and an Objective Advisor – Mindset is as Important as Talent

Each member of the team had to be comfortable with all aspects of game development. Everyone was responsible for their own programming, art, sound, and everything else that went into the final product. But talent wasn’t everything. Ideally, it was important for everyone to approach this style of development with the understanding that design is paramount – everything else from art to engineering exists only to serve the final design. A great engineer without this mindset would likely be less successful than a mediocre engineer who fully understands this point.

A word from Jesse Schell, project advisor: “I am always fascinated by the creative process for generating new game ideas, and so naturally I was thrilled when Shalin, Matt, and the Kyles proposed this project. I looked at it as an opportunity to try side-by-side controlled experiments in creativity, hoping there would be useful game design lessons learned. As faculty advisor, I tried to make sure that the team tried several different techniques, that the team was learning from their mistakes, that no one dwelled too long on an idea that wasn’t working out, and that each individual was finding their optimal creative process.

“I gave suggestions along the way about how to improve the games as well, but mostly I tried to stay out of the way. I felt a bit like a gardener — I did a little watering and weeding, but the flowering was all up to them. As this paper shows, the team was able to make some very useful conclusions – and ended up with some good games to boot! There is still more to learn about optimizing the creative process, and the Carnegie Mellon Entertainment Technology Center plans to continue this project.”

Develop in Parallel for Maximum Splatter

So once we assembled our team, what did we do? We stop working with each other! It might sound odd, but the benefits of not collaborating were too great to ignore:

Risk Mitigation – By developing four prototypes simultaneously, we could make risky design decisions with the comfort that at least one or two were likely to be successful

Friendly Competition – Everyone benefited from being kept on their toes. Like capitalism!

Wider Thematic Exploration – Four minds all focused on the same theme forced us to plumb the depths of each topic. How embarrassing it would be if we all made the same game! This forced us into some rewarding creative realms and allowed us to avoid obvious points of attack.

Sharing and Caring – Though we didn’t share code (by choice, not requirement), we found it helpful to share concepts and understanding into a cumulative pool of knowledge. If one team member, for instance, discovered an effective way to represent spring systems, everyone would benefit.

As the weeks wore on, we found that having the team work together was most valuable at the beginnings and ends of each cycle. In the beginning of each cycle, the team was useful for helping to solidify and compare ideas. Once we hit development, we found each other to be more of a distraction than anything else – as each person was fully immersed in their own efforts. By the end of each cycle, we would all return to the room and work together until the wee hours of the morning for that last-minute extra taste of competition. A graph of this phenomenon might look something like this:

2. Design: Creativity and the Myth of Brainstorming

A great idea takes a split second to happen, but waiting for that lightning to strike can be excruciating. There’s no such thing as forcing a great idea to squirt out, but this section should help cultivate your creative juices.

Formal Brainstorming Has a 0% Success Rate

We tried hard – boy we really wanted brainstorming to work! We scheduled “brainstorm meetings”, and “powwows”, we tried different color markers on whiteboards and oversized post-it notes, we even used motivational phrases like “blue sky” to help with our “out of the box thinking.” But in the end, out of all the games we created, not a single one was the result of sitting down as a group for a brainstorm session.

Why not? This was all very shocking to us, but after much investigation, it appears that you just cannot schedule creativity. You cannot say, “Hey everybody let’s meet for a brainstormer at 4:15, and by 5:00 we’ll have 4 kick-ass game ideas ready to hit the ground running!”

But it’s not hopeless. There are still (at least) two reasonable things you can expect from a well-conducted brainstorm session. The first, of course, is that it gets everybody thinking. And then sometime later, maybe on the drive home, or in the shower, or while taking Poopy for a walk, a brilliant idea will erupt in your head. Or maybe not. But as far as we can tell, your mysterious brain does a lot of thinking when you least expect it.

The second way we found brainstorming to be useful was when there was something concrete to talk about. For example, “How can we improve this?” as opposed to “Hey let’s come up with something arbitrary!” Given a half-formed game idea, for instance, it was moderately helpful to run it by the rest of the group to flesh it out.

Everyone is a better critic than a creator, right?

Gather Concept Art and Music to Create an Emotional Target

As an alternative to brainstorming, we found that gathering art and music with some personal significance was particularly fruitful. People have commented that many of the games like “Gravity Head” or “On a Rainy Day” create a strong mood and have strong emotional appeal. It’s no accident. In these and many other cases, the soundtrack and initial art created a combined feeling that drove much of the gameplay decisions, story, and final art.

Mr. Gabler: “The idea behind “Tower of Goo” came up while I was listening to (for some reason) the opening to Astor Piazzolla’s “Tango Apasionado” after walking home, and had this drizzly vision of a town at sunset where everyone was leaving their houses, carrying out chairs, tables, and anything they could to build a giant tower in the center of their city. I didn’t know why exactly, but they wanted to climb up and up and up – but they weren’t very good civil engineers so you had to help them. The final prototype ended up a little more cheery, and I replaced the final music with Piazzolla’s more upbeat “Libertango”, but here’s a case where an initial emotional target basically wrote the entire game.”

Simulate in Your Head – Pre-Prototype the Prototype

It’s really easy! All you have to do is imagine your game audience saying, “Wow!” And then just work backward and fill in the blanks. What’s making them enjoy your game? What emotion are they feeling? What is happening in the game to make them feel that way?

For each of our most successful games, it was never a surprise when they ended up being fun to play – in the best cases, we knew before touching a line of code that the idea was solid, because we had run a simulation of the game as a little thought experiment beforehand. The reverse is also true. There was no game that accidentally or unexpectedly became successful. We always knew ahead of time. (Unfortunately this didn’t keep us from pursuing half-baked ideas.)

Simulating in your head also makes the development of the final prototype really easy. Since you will know exactly what you will be making, you won’t waste time making expensive trial and error “design decisions” by noodling around in code.

One team member admits: “It wasn’t unusual to blow the first 3 or 4 days of the week just fooling around watching O-Zone music videos for “inspiration” or propped upside down in a bean bag listening to music and filling my head with blood occasionally running some crappy brain simulations. Finally Thursday or Friday would roll around and I’d panic because I still had no idea what to turn in for Monday, so I’d take the strongest of the ideas and tweak it based on whatever the obsession of the week was until it felt like a fun game, then stay awake for the next few days typing it all into a computer and drawing beautiful pictures. For me, (and I think all of us) the days spent in “pre-production” were unquestionably more valuable that the days spent in actual development.”

3. Development: Nobody Knows How You Made it, and Nobody Cares

Once you come up with a great idea, here are some tricks to whip up a little demo in no time!

Build the Toy First

Start with the core mechanic. Whether spring systems, swarm behavior, gravity, etc, it never took more than a few hours to get the basic theme up and running. This “toy” should be the core mechanic of the game minus any goals or decisions. There is no win or lose state, just a fun thing to play with.

Mr. Gabler: “With “Super Tummy Bubble”, the “toy” was just a bunch of bubbles suspended in a little container. After playing with the toy and flinging bubbles around for a while, I got it tuned to a point where sticking my fingers in bubbles felt really satisfying, so it was time to slap on some gameplay. Gameplay features in this case were bubbles of different parasite types, a concept of “popping”, a concept of “chains”, score counters, etc.”

If You Can Get Away With it, Fake it

This is arguably one of the most important lessons of the project. Often the “correct” solution is not the best solution. Strategically faking it will save you time and money; it will make your game faster, and your teeth whiter. Fake it liberally and often! Don’t set up complicated lighting and shadowing when a simple drop shadow and baked textures will be just as effective (“Darwin Hill”). Don’t set up a complicated pattern recognition system for analyzing a user’s drawings when you can fudge it with the same effect (“Suburban Brawl”). Don’t draw splines or create your own vector art library when quickie stretched bitmaps give same effect faster and easier (“Tower of Goo”). This rule is also a fantastic general lesson for life, we have found. Slackers, take note.

Cut Your Losses and “Learn When to Shoot Your Baby in the Crib”

At the beginning of the project there was a desire to salvage everything – a little more time and effort and surely a crappy game would become a work of genius! One such doomed prototype began as a beautiful spring system that squished and stretched and made you want to grab it and pull it all over the place, but it just wasn’t become a compelling game. The original spring system mechanic took just a few hours to create, but then it flared and consumed an additional wasted week of coding and re-coding in a sad attempt to force the mechanic into becoming a game.

It’s important to quickly recognize dead-end game ideas, cut your losses and move on. As we found, spontaneity is more valuable than time spent trying to salvage existing code. You can always come back if lighting strikes at a later time.

Mr. Kucic: “My “Potato” ended up being a perfectly simulated soft body system built in Flash. The only problem was that it was in no way fun. It caused more headaches than death metal, wasted a week, and it didn’t even really move. You’ve got to know when to hold ‘em and know when to fold ‘em.”

Heavy Theming Will Not Salvage Bad Design (or “You Can’t Polish a Turd”)

We found that game players are smarter than you think, and they can tell when you’re pulling a fast one on them. If the gameplay is horrible, there is no recovery – all the art, music, and product tie-ins in the world won’t make it a great game. Like taking a stale gameplay mechanic and slapping the latest 3D animated movie characters on it, nobody will be fooled.

Mr. Gray: “With “Spin to Win”, the ‘gameplay’ was to rotate your mouse to spin multiple circles – literally disc spinning. To hide the fact that it wasn’t fun, I heavily themed the game with a ’60s Bewitched art style and music. But no matter how much I polished the game, it still wouldn’t shine. Despite all the extra love, it quickly became one of the site’s most hated games.”

But Overall Aesthetic Matters! Apply a Healthy Spread of Art, Sound, and Music

This is actually counter to one of our original hypotheses. We didn’t think art or sound would make any difference at all, but we were wrong! Playing with a well-polished game actually feels better in your hands than playing the exact same code but with careless art and poor sound. It is important to make the following distinction though – polishing the aesthetic (as in the above section) will still not salvage bad design, but it does have the power to make a good game even more playable. This does not mean that you need fancy graphics or surround sound. It does mean that you can benefit from pulling everything together into a tight cohesive compositional package. Remember, even “crappy” can be a tight winning aesthetic if you frame it the right way.

Nobody Cares About Your Great Engineering

Again, it’s worth noting that a great engineer does not necessarily make a great prototyper. “Correct” or “reusable” solutions are often not what we look for in quick throwaway code. For every problem, you should be able to come up with a large handful of solutions and be prepared to pick the one that gets the job done – fast. The end user will never see your great engineering, and they don’t care.

Mr. Shodhan: “By over-engineering, it’s easy to end up with generic tools or technology demos that never translate into something playable. This can be likened to a rock star executing a technically brilliant but entirely self-indulgent guitar solo that leaves the audience yawning! For the “evolution” round, I made a program with subdivision surfaces and a cell shaded look for evolving 3D models by cross breeding ancestry trees. There was a lot of cool technology, but it had absolutely no gameplay!”

4. General Gameplay: Sensual Lessons in Juicy Fun

In addition to learning the hard way about rapid prototyping, we also stumbled over some general gameplay guidelines. The following are a collection of some that significantly add to that “fun” experience.

Complexity is Not Necessary for Fun

If mankind can entertain itself for literally thousands of years with variations on the theme of “ball and a flat surface”, we might be trying too hard with some of this new-fangled video game stuff. It’s entirely possible to have fun with basic primitives, think Tetris, Pac-Man, and any classic arcade game. Like the Romeo and Juliet love story archetype, these games had mechanics so good we’re still reusing them again and again decades later. Lens flares, bump mapping, camera bloom, and other amazing new technologies are nice, but won’t make your game more fun. Prove to yourself that your core mechanic is worthwhile with a simple prototype. Once you’re convinced, then you can make it pretty.

Create a Sense of Ownership to Keep ‘em Crawling Back for More

We discovered quite accidentally that the games with the greatest replay value were the ones that had some sort of creation or customization aspect. For instance, “make a creepy tree out of hands and umbrellas”, or “draw your own house”, or “build your own tower”, or “evolve your own race of mutated creatures”. Apparently this is a well-known phenomenon and has something to do with all those create-a-face features common in many recent games, and customizable cell-phone ring tones, and those “be different, express yourself like everyone else” advertising campaigns. So jump on the bandwagon! Create a sense of ownership to keep ‘em crawling back for more.

“Experimental” Does Not Mean “Complex”

Early in the project, many of the games we made were far more complicated then they should have been. Not only was the UI confusing, but the ways in which keys mapped to actions were not natural or intuitive. Unless we could minimize the confusion time before the “oh I get it” moment, we knew we risked that players would get frustrated and never play the game again and possibly never come back to our site. Luckily, we found it was possible to be “experimental”, and still be easy to understand.

Mr. Shodhan: “My first round game “Spaceball Munch” was a 3D version of the old “Gorillas” game where you specify an angle and a velocity at which one gorilla throws a banana at another. Not only were you now in 3D, but there was arc ball camera rotation and the game was on a spherical field. So there were two angles and a velocity to worry about. Oh, and it was no longer a discrete turn-based game but you controlled a continuous stream of particles and had to hit all these moving objects. Here is a screen shot of the gratuitous variable wastage.”

Build Toward a Well Defined Goal

A well defined goal was embarrassingly easy to forget about. Without a gameplay goal, a prototype is just a toy – not a game. For some reason, people seem to enjoy having the opportunity to fail. A goal can be anything – like “collect x number widgets in a x amount of time,” or “keep the system stable,” or “traverse a space without touching anything bad,” but it was difficult finding a goal that didn’t feel a little tacked on, (like anything involving a “time limit”). The best goals, we found, were an innate part of the gameplay like in “Tower of Goo,” where the implicit goal was to simply “build up”.

“Tower of Goo” – building toward a goal… and beyond!

Make it Juicy!

“Juice” was our wet little term for constant and bountiful user feedback. A juicy game element will bounce and wiggle and squirt and make a little noise when you touch it. A juicy game feels alive and responds to everything you do – tons of cascading action and response for minimal user input. It makes the player feel powerful and in control of the world, and it coaches them through the rules of the game by constantly letting them know on a per-interaction basis how they are doing.

Some juicy examples you may have experienced might include:

Alien Hominid – enemies exploding and flinging blood to an almost unjustified extent

Mario Bros. – bouncing through a room full of coins, blinging with satisfaction

Pachinko – a never-ending gush of balls all under your control

Super Puzzle Fighter II Turbo – animation and sprites abound on multiple chains

Juice feel sgreat!You can’t keep your hands out of it.

Final Thoughts

The Experimental Gameplay Project team was a thrill to work with. We hope that the next time you try something new or a little crazy these tips and tricks come in useful for you. Who knows, that little idea you had this morning could be the next big thing. Pull some friends together, or go solo, but try and prototype it! You might surprise yourself.

Our objective advisor kindly pointed out, “Rapid prototyping can be a lot like conceiving a child. No one expects a winner every time, but you always walk away having learned something new, and it’s usually a lot of fun!”

Happy prototyping!

Handy Cut-Out List!

Setup: Rapid is a State of Mind

Embrace the Possibility of Failure – it Encourages Creative Risk Taking

Enforce Short Development Cycles (More Time != More Quality)

Constrain Creativity to Make You Want it Even More

Gather a Kickass Team and an Objective Advisor – Mindset is as Important as Talent

Develop in Parallel for Maximum Splatter

Design: Creativity and the Myth of Brainstorming

Formal Brainstorming Has a 0% Success Rate

Gather Concept Art and Music to Create an Emotional Target

Simulate in Your Head – Pre-Prototype the Prototype

Development: Nobody Knows How You Made it, and Nobody Cares

Build the Toy First

If You Can Get Away With it, Fake it

Cut Your Losses and “Learn When to Shoot Your Baby in the Crib”

Heavy Theming Will Not Salvage Bad Design (or “You Can’t Polish a Turd”)

But Overall Aesthetic Matters! Apply a Healthy Spread of Art, Sound, and Music

Nobody Cares About Your Great Engineering

General Gameplay: Sensual Lessons in Juicy Fun

Complexity is Not Necessary for Fun

Create a Sense of Ownership to Keep ‘em Crawling Back for More

“Experimental” Does Not Mean “Complex”

Build Toward a Well Defined Goal

Make it Juicy! (gamasutra)

浙公網安備 33010602011771號

浙公網安備 33010602011771號